By Nastasia Boulos

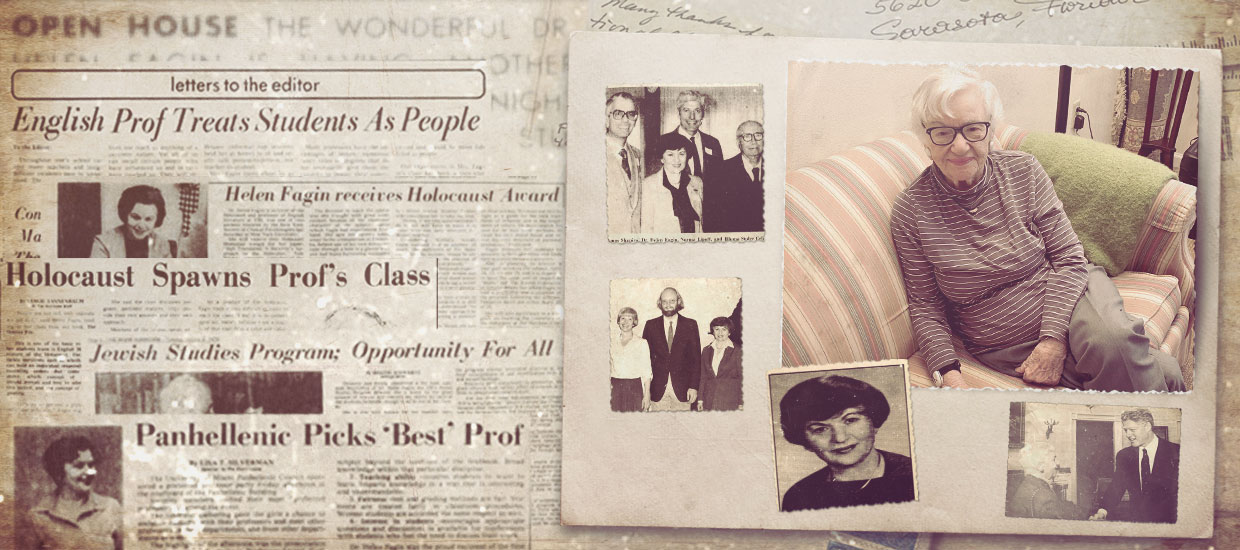

A centenarian, wearing big pearl earrings and black-rimmed glasses, Helen Fagin welcomes me into her home and in her face, there is warmth. When she hugs me and thanks me for visiting, there is goodness and humility. And when she speaks of her life and time as a teacher, there is excitement, and pride, and a little bit of humor.

Dr. Helen N. Fagin, A.B. ‘66, M.A. ‘68, is a Holocaust survivor.

She was in her second year at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland when the war began. Soon thereafter her parents were sent to the Treblinka concentration camp, where they perished. Fagin and her two sisters survived, spending five years between ghettos, separated then reunited.

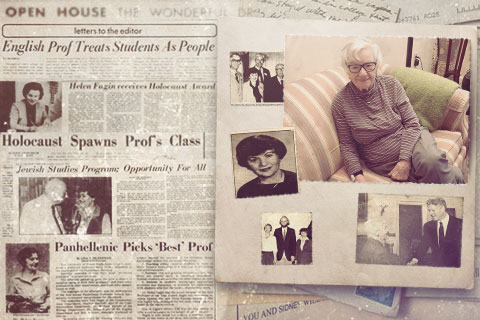

When she arrived in New York City in 1946, Fagin spoke little English. By 1971, she had joined the University of Miami’s English department faculty, having obtained a scholarship and completed both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees there. She had rapidly established herself as a dedicated teacher and community member, winning both the Freshman Teacher of the Year and the Panhellenic Council Best Professor awards.

And she was a favorite amongst students. In a Miami Hurricane letter to the editor, a group of students wrote: “Mrs. Fagin cares about us as people, not as numbers or just as faces. She is teaching us the concept of morality towards other human beings; showing us the wrongs of man’s inhumanity to man and how we can correct the embedded philosophy. She teaches us by showing us.”

Her open houses, held regularly in her home, were immensely popular. There was an open fridge (no liquor), a ping-pong table and a pool table. At a time when tensions over race, religion and the Vietnam War were high, students had a place to come together and talk.

But for over 20 years Fagin had rarely, if ever, spoken of her own experiences, the memories too painful to share. That changed, however, when Night author and future Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel was invited to speak at the UM Hillel House. Fagin was asked to hold a reception in his honor at her house. It was there that he encouraged her to talk about her experiences so that others would not “describe it from their imaginations.”

Fagin, who had organized clandestine classes for girls in the ghetto in Poland, began inserting Holocaust literature into her English classes at UM, eventually developing a curriculum for her Literature of the Holocaust class–one of the earliest of its kind in the nation. More than simply encouraging students to analyze and critique writers’ works, Fagin concentrated on teaching a moral lesson. “I became strongly convinced that the Holocaust could serve as a constructive lesson in teaching personal morality to young men and women,” she said. The fact that she herself was a survivor made the lessons all the more poignant.

The course also became a part of the newly created Judaic Studies program at UM, which Fagin fought to make an interdisciplinary major. She became its director in 1978, after receiving her Ph.D. in 1977. Under her leadership, the program grew and regularly sponsored conferences and talks. She created a student exchange program with Tel Aviv University and established the Handleman Holocaust Collection with books she obtained in her travels.

Throughout the years, she has participated in national and international conferences. In 1979, she became an adviser to Wiesel in developing the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. She was also instrumental in the creation of the Miami Beach Holocaust Memorial and the Florida Holocaust Museum in St. Petersburg, FL, and served, at the request of President Bill Clinton, on the committee that created the World War II Memorial on the Mall in Washington, DC.

“Only proper education of future generations could prevent the probability of another holocaust,” Fagin writes. Three million Polish Jews–90 percent of the prewar population–were killed during the war. In all, the Nazis persecuted and murdered six million Jews and millions of other victims between 1933 and 1945–a constant reminder of what human beings are capable of doing to other human beings.

But out of an experience filled with hatred and cruelty, Fagin created and implemented lessons of compassion and understanding, of tolerance and inclusivity. She has forced us to examine our own prejudices. And she’s inspired her daughter, Judith, who has honored her legacy by setting up the Dr. Helen N. Fagin Holocaust Education Endowment Fund at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Decades after leaving teaching, her Sarasota home is still filled with plaques, awards, and letters from students. An email from a former student, the only non-Jewish person in a Jewish fraternity, sums up her contributions to the world: “Thank you Dr. Fagin for making me a better student, a better teacher, a better doctor, a better Christian, and a better human being.”